Haruki Murakami's 'Portrait in Jazz'

Translating an essential work about jazz by Haruki Murakami and Makoto Wada

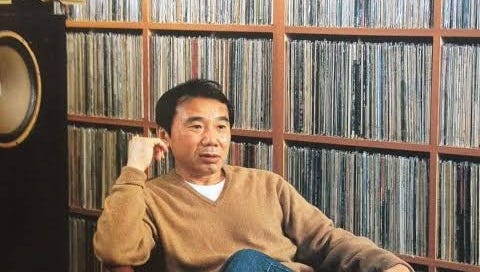

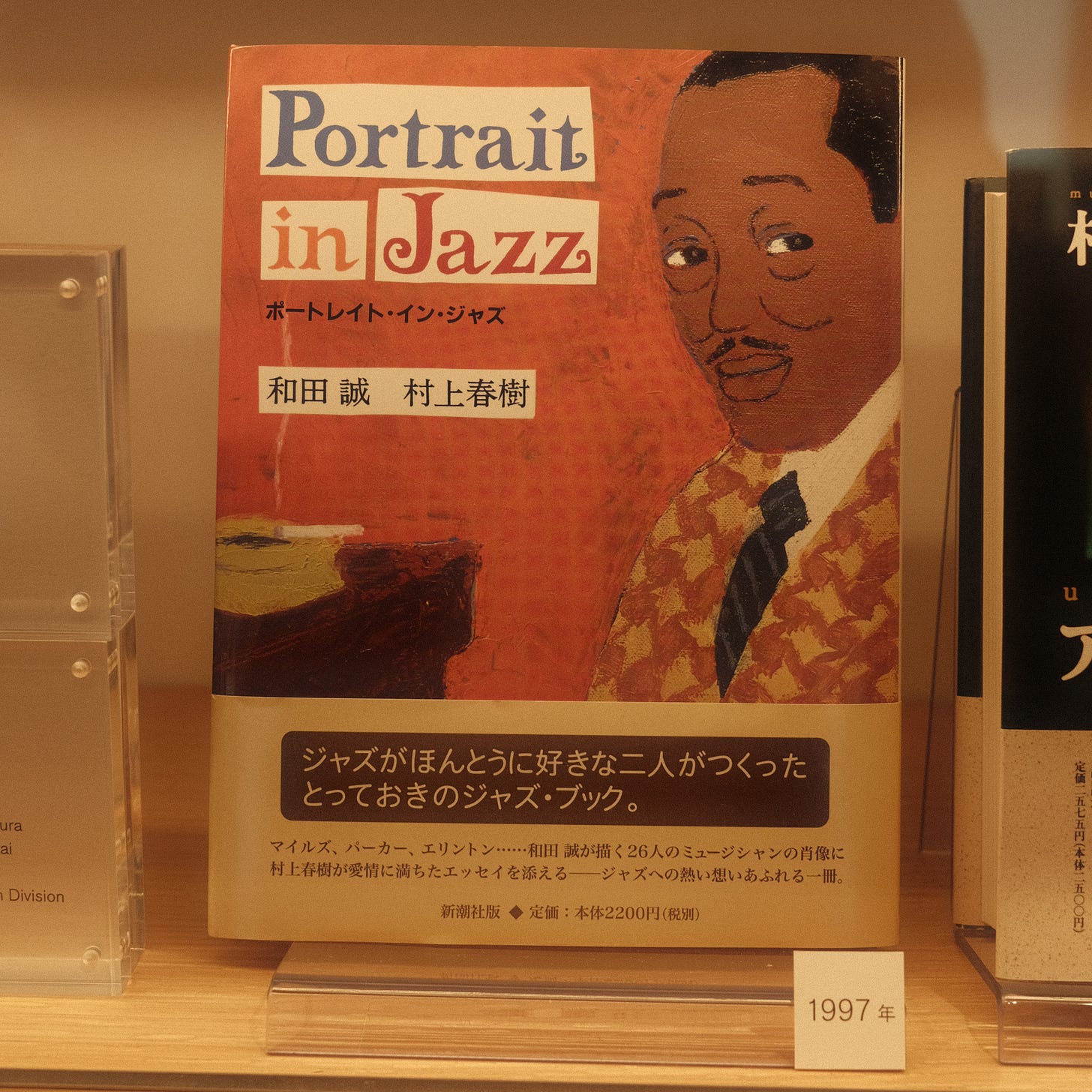

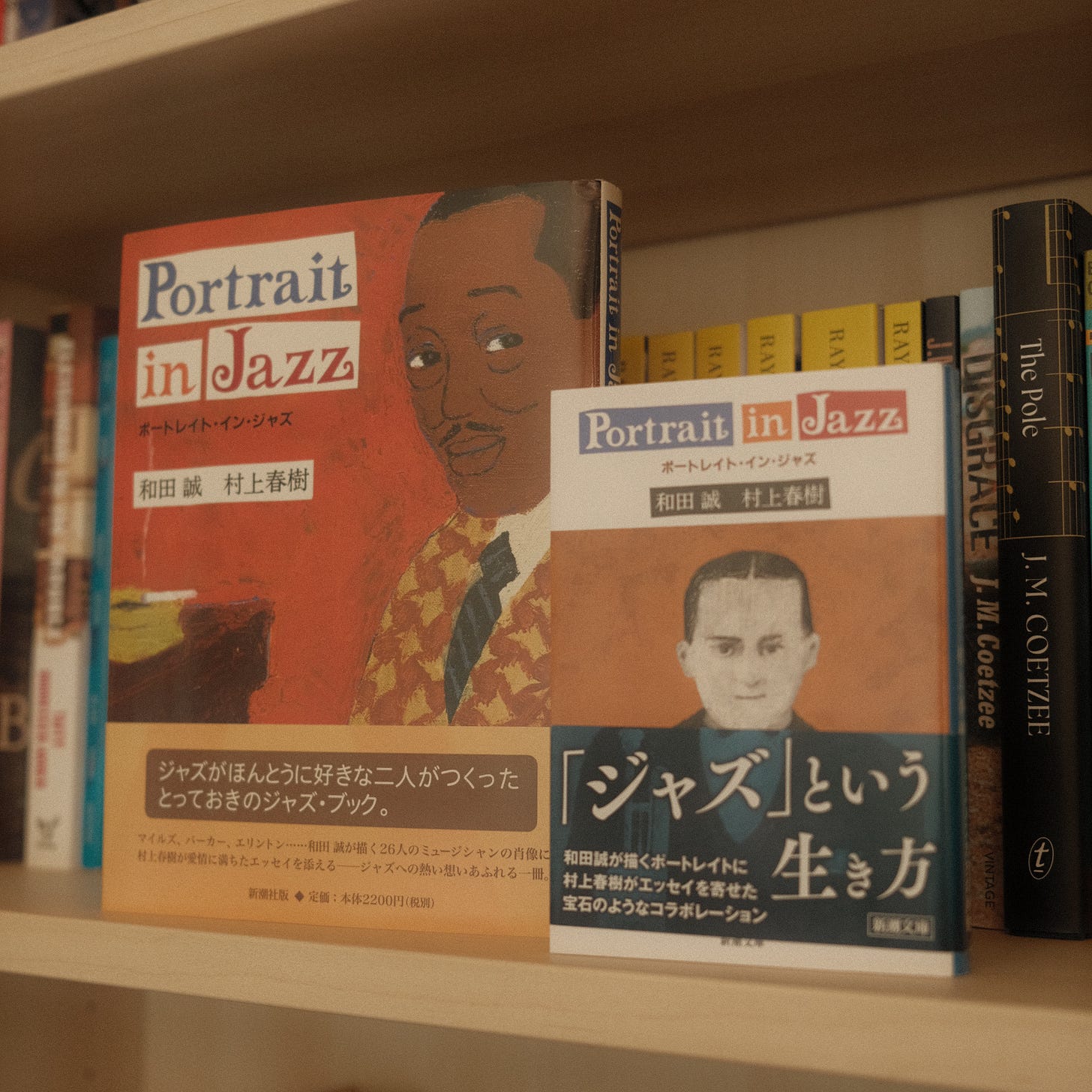

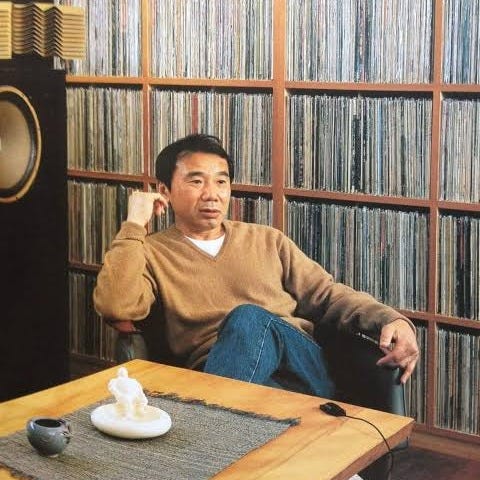

I recently installed a couple of new bookshelves in my study and I was surprised to see that my Haruki Murakami collection, made up of every single one of his releases (some I’ve even got two or three copies of) takes up almost three entire shelves. Over more than a decade I’ve collected and read them all aside from one: Portrait in Jazz, Murakami’s love letter to jazz music split across two volumes. The book was first released in 1997 and has never been translated into English.

Before I left for Japan in October last year I made a shopping list and had a copy of this book very close to the top. While it took me the very best of three weeks to source a copy, I actually arrived home with two. The first is a second-hand hardcover of Volume 1 that I found in Disk Union Shinjuku and the other is a brand new smaller softcover edition that I found in Kinokuniya near Osaka station that combines both Volumes 1 and 2.

I bought them really just to own. To cross off my list and fit them into their assigned spaces on my bookshelf. But actually, why not translate what I can now that we have the technology and at least learn some things about jazz, Murakami, Japan, and anything else that I may not otherwise learn? So that’s what I’ve done and I thought I’d bring you along for the ride. I’m obviously not going to translate the entire thing here, but I’ll share some key points and anything I’ve learnt. For the sake of brevity, let’s stick with Volume 1 for now.

I’ll start with a disclaimer. I can’t speak or read Japanese so I can’t confirm the accuracy of the translations that I’ve done using Google Lens. But it seems close enough at the very least until we hopefully get a proper translated edition in English and other languages.

“A special jazz book created by two people who truly love jazz.”

Portrait in Jazz is a fairly simple book. It’s the work of famed Japanese author Haruki Murakami, but also just as much of Makoto Wada, who illustrated the book’s incredible images. Wada was an illustrator who designed pieces for magazines and newspapers in Japan, but he was also a filmmaker and even made a film about jazz called Round About Midnight. You can watch here.

In terms of layout, the book is very straightforward. There’s a preface by Wada and an afterword by Murakami and in between it dedicates four pages each to 26 different jazz artists. These pages include a short reflection by Murakami, one of Wada’s illustrations, and an essential record by the artist. In this post, I’ll look at the preface, three of the artist profiles, and the afterword. If you enjoyed it and want me to cover some of the other profiles, just let me know.

Preface by Makoto Wada

Makoto Wada introduces his love of jazz by first speaking of his love of film when he was in high school. One day, he saw a film called Hit Parade, which featured performances by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Louis Armstrong, and Lionel Hampton and kickstarted his love of swing just before the boom of bebop. He said, “I couldn’t help but listen to the new jazz.”

It was when Wada was in college that Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis became big names but he enjoyed listening to different types of jazz from different eras. Even in his profession as an illustrator, he chose films and music to be themes of his work, including a solo exhibition called ‘Jazz’ which featured paintings of 20 different jazz musicians. This caught the eye of Haruki Murakami who agree to contribute accompanying essays later becoming Portrait in Jazz.

Wada finishes by stating that Murakami’s passion for jazz is deeper and more passionate than his was and he’s thankful that through Murakami’s writing his paintings could live on.

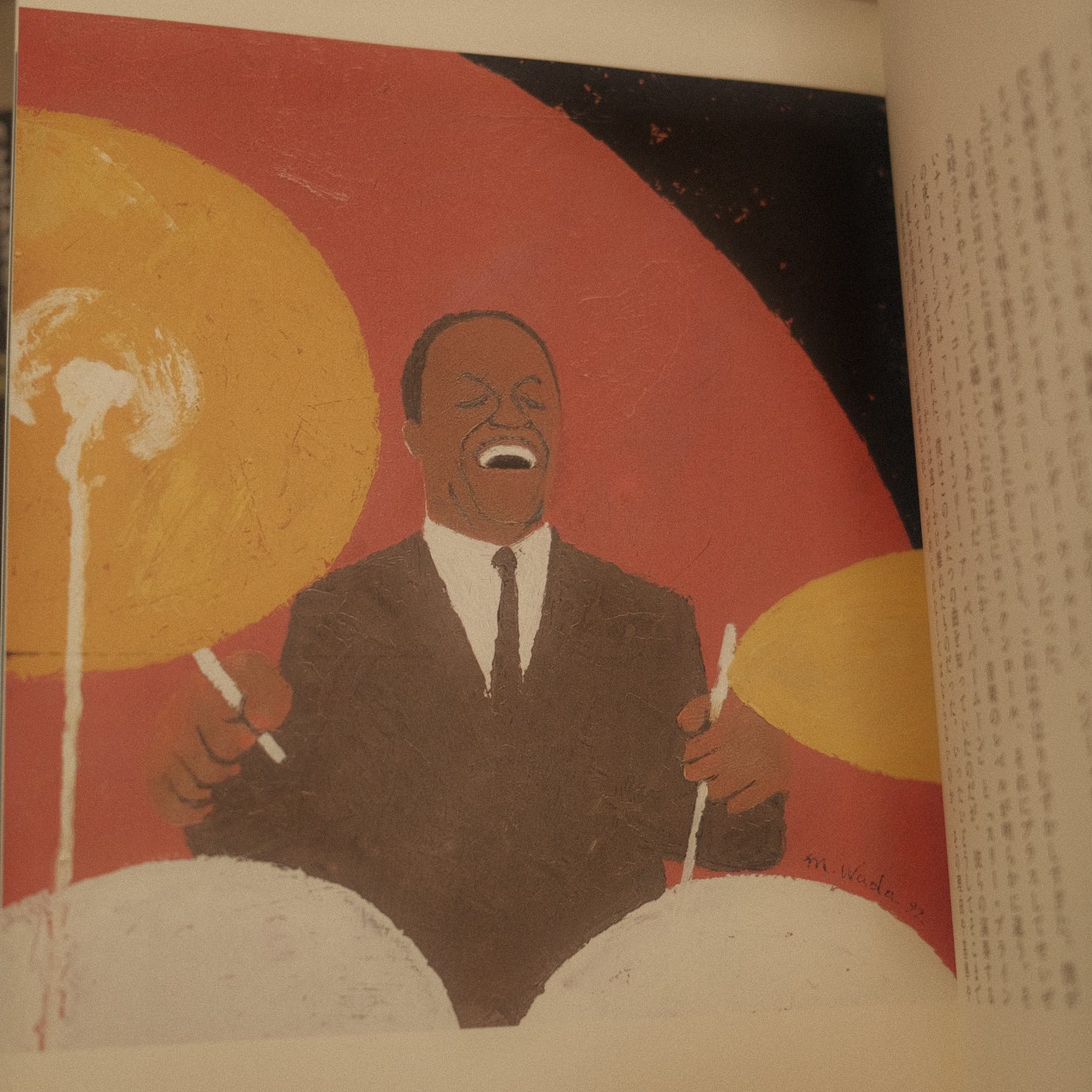

Art Blakey

Haruki Murkami’s first exposure to modern jazz was at a concert by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers on a cold January day in Kobe in 1963. He was just a high school student and didn’t know much of what jazz was about, but curiosity got the better of him and he bought a ticket, perhaps due to the fact that foreign musicians rarely performed in Japan or because the Jazz Messengers had somewhat of a good reputation.

Speaking of his experience, Murakami said, “As for whether I understood the music I heard that night, it was too difficult. At the time what I listened to on the radio and records was mainly rock and roll, plus Nat King Cole at most, so the level of music was clearly different.”

Murakami knew some of the songs they played but the melodies were different from the ones he knew and he couldn’t understand the reason why they were “destroyed and distorted so thoroughly.” The concept of improvisation was not something he knew anything about.

“There was something here that pierced my heart. I instinctively felt that, even if I couldn’t fully understand what I was seeing, it was something that held new possibilities for me. I think this was because the music itself was full of energy, forward-thinking, and soul,” Murakami said.

Right after the concert, he went out and bought records from Blakey’s slightly earlier period and listened to them over and over. Whenever he listened to these records, it is this era that floods back to him.

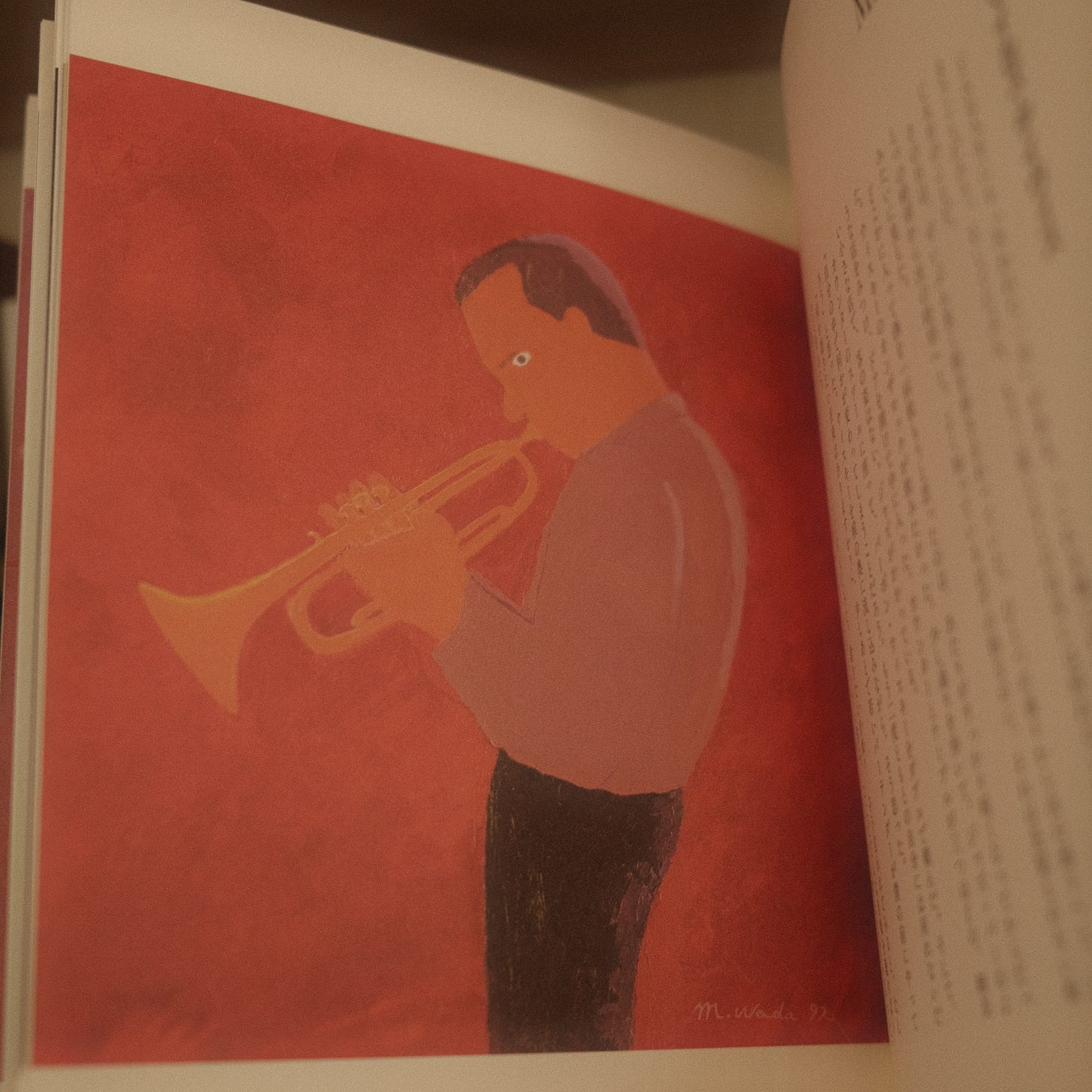

Miles Davis

Murakami dedicates the section about Miles Davis to an experience he had one night at a jazz bar where he requested Miles’ 1964 live album “Four and More” thinking first of the record’s dark, gloomy cover. For him, it was exactly the music he was looking for and the only music he needed at the time.

“It was already completely dark when I decided to go in and have a drink. I wanted to drink whiskey on the rocks. I walked down the street a little and found a place that looked like a jazz bar, opened the door and went in. It was a long and narrow shop with a counter and there were no customers. Jazz was playing. I thought to myself, “Something will change inside me. I will never be the same again,”” he said.

Murakami speaks of Miles’ playing on the record as deep and poignant, with tempos so fast they are almost brawling. To Murakami, Miles asks for nothing and can give nothing and there is only an act in the purest sense of the word.

Speaking about the power of jazz and the influence of Miles Davis, Murakami ends with: “I realise that I didn’t feel any pain in my body. At least for a little while, while Miles was there slicing away like an obsessive. I ordered another whiskey. It was a long time ago.”

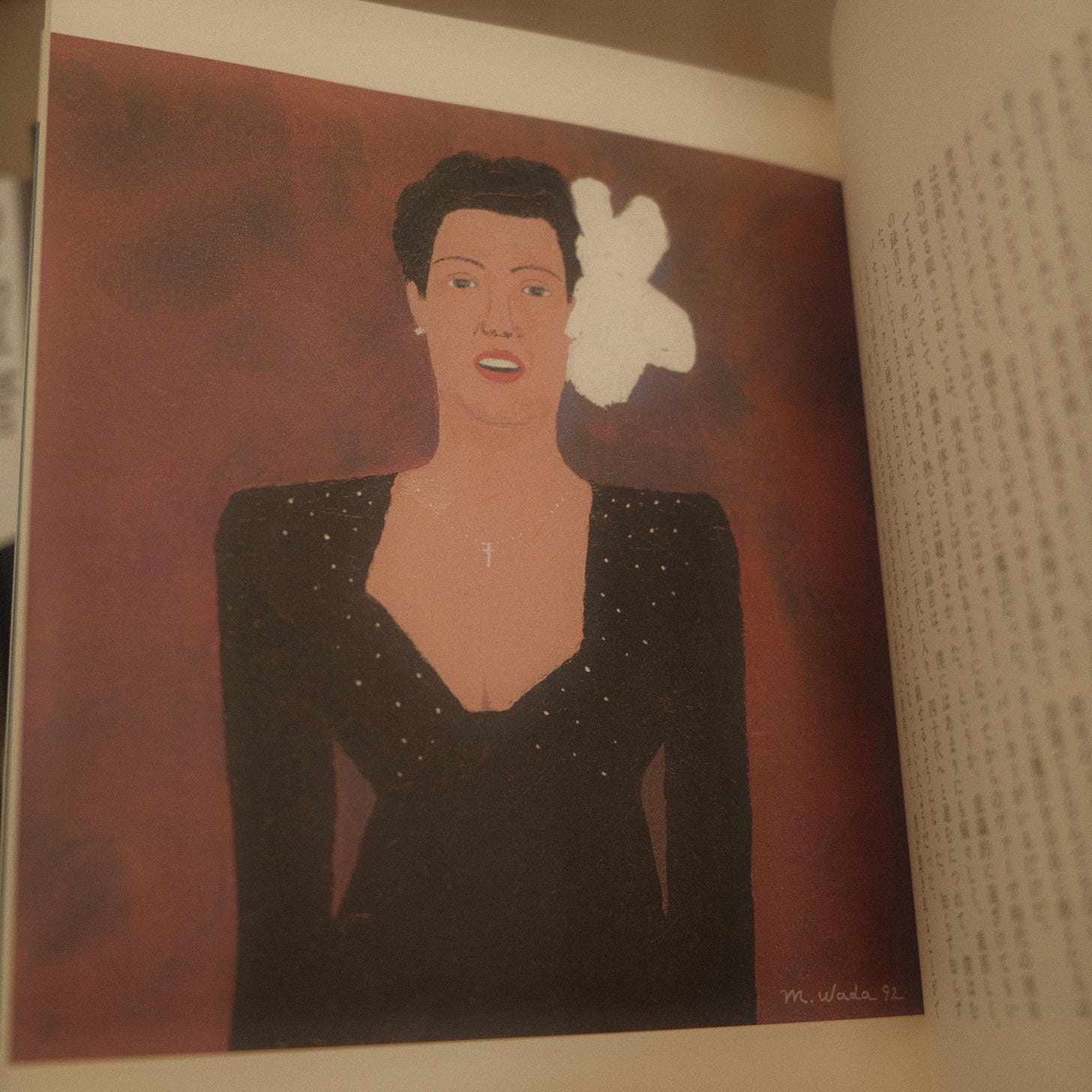

Billie Holiday

Billie Holiday was one of Haruki Murakami’s early musical heroes. However, it wasn’t until he was older did he realise how great of a singer she actually was, despite having been moved by her music from a young age. Murakami attributes this to the wonder of growing older.

Speaking about Holiday, Murakami said, “The world swung along with her swing. The earth itself swayed. I’m not exaggerating. It wasn’t art, it was magic. As far as I know, the only other person that could use that kind of magic freely was Charlie Parker.”

Murakami used to exclusively listen to her earlier recordings purely for the fact that she had a young and fresh voice that was not yet lost to drugs. As he got older though, he began to crave her 1950s output, first thinking they sounded too painful, oppressive, and pathetic, but later coming around to her “broken singing” as he calls it, but not quite knowing what drew him in.

“When I listen to Billie Holiday’s songs from her later years, I feel as if she is quietly taking on all the mistakes I have made and all the people I have hurt through my life and through my writing and drinking it all up. She is telling me to just forget about it,” Murakami said.

Afterword by Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami says it as simply as: “One day, I was fascinated by jazz music, and since then, I have been living with this music for most of my life. Music has always been very important to me, but jazz has a special place in it.”

However, he says the act of writing about jazz he finds daunting and overwhelming just by the sheer fact of how much there is to write about and he would have no idea where to start.

So it was a blessing that he came across Makoto Wada’s illustrations which immediately inspired him. He said, “When I look at Mr. Wada’s paintings, I can sense the unique melody that permeates the musicians. The images just popped into my head and I had to translate them into words.”

Murakami ends the afterword by highlighting how impressed he was at the selection of musicians Wada chose to illustrate, omitting icons such as Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane for more obscure picks like Jack Teagarden and Bix Beiderbecke. Murakami gushes over Wada’s love for jazz just as Wada did the same for Murakami in his preface.

Portrait in Jazz is not just a paean to jazz, but a dialogue of respect between two like-minded artists.

Thanks for reading! I had fun with this one and I was so glad to finally be able to read through this. If you enjoyed it and would like to see another part with some of the stunning artwork, just let me know. For those interested, the full list of musicians covered in Volume 1 of Portrait in Jazz are:

Chet Baker

Benny Goodman

Charlie Parker

Fats Waller

Art Blakey

Stan Getz

Billie Holiday

Cab Calloway

Charles Mingus

Jack Teagarden

Bill Evans

Bix Beiderbecke

Julian Cannonball Adderley

Duke Ellington

Ella Fitzgerald

Miles Davis

Charlie Christian

Eric Dolphy

Count Basie

Gerry Mulligan

Nat “King” Cole

Dizzy Gillespie

Dexter Gordon

Louis Armstrong

Thelonious Monk

Lester Young

Album of the week time! Let’s stay on theme and go with Lady In Satin by Billie Holiday. What a voice she had.

Truly wonder why it has never been translated…. Maybe a job for me in Japan is get a translation in print!

As a jazz fan and an artist, I really enjoyed this post!